Texts: 2016

RoseNose

RoseNose

Rhyme is how a poem reproduces. Autopoesis occurs as a proliferation of the same, the same sound of a syllable, a word ending. It repeats and differentiates within a narrow phonetic regime. It is the poem’s way of making itself continue, of shuffling through language in order to bring about more itself—form, norm, storm; shocked, mocked, knocked, locked; rose, nose.

The rhymes generated for the work’s sound piece are improvisations; the readers are searching for a next, a possible word that rhymes with the former. Word choice appears to be arbitrary. Content instead arises where sounds and syllables speak as bodies to another, as forms that solidify when they meet their word-opponent. One word is being pushed towards the next, into a continuum that spills language into the future, into the open space.

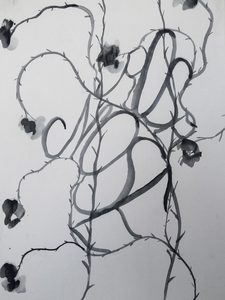

Two bodies, male and female, are sealed in latex that is smooth and reflective like a mirror. The surface properties of the latex echo those of the PVC strip curtains that are draped in the exhibition space to create areas of enclosure. Growing on the vertical slats that frame these compound structures are thorns, roses and vines; words and calligraphy; NoseRose. Plaster casts of these bodies are enclosed in a latex vacuum bed, which seals the naked body completely, making indi- vidual detail highly visible. It is a form of clothing that reveals everything of the naked body while covering it in its entirety. The nose is covered and air only flows through a small straw that is attached to the mouth.

George Segal’s expanded sculpture “Alice listening to Her Poetry and Music” (1970-71) casts the entire body of poet Alice Notley in a sitting position with one hand cupping her chin. The poet is sitting at a table, listening to the record- ing of her own poems. Poetry here appears as an agent in the work’s temporal expansion. Other than the sculpture, which has achieved the status of an irreproducible, finite object, poetry is being constantly reproduced in space, reread and sent through a loop of repetition that makes it endure in time. It is curious to note, however, that Segal made this sculpture of Alice Notley when she was young. The cast does not preserve the body as a finite, dead form. Rather, it fixes it in a moment of its aliveness, on the brink of its becoming. Notley was still becoming the celebrated poet she is today; Segal memorialized her before that.

In the more recent poem “The Gift” (2015), Alice Notley now remembers speaking to her dead father, whom she con- jures. The poem summons a language that survives, a language that speaks from the other side, from us as we once were, and us awake still, or again. In the audio recording of the reading, Notley adds narrative autobiographical elements. The poem is read repeatedly, and interrupted by conversations with an imagined reader that explains the biographical origin of phrases and words in the poem. The entwinement of these poetic speech registers with a highly personal description of the history of the poem’s creation serves as cue for the formal arrangement of the sound piece in “The Rhyme”. “The Rhyme” reveals remnants of the situation when it was a work in progress. The bodies of friends that were cast in plaster, and the conversations that the artist had with them during the casting sessions now belong to a formally more stringent, metric environment.

It’s the reclining position, lying on the chair like that and having your body patted, patched up and wrapped with warm, moist cloth, that gets you talking. And you can’t stop. We were looking at photographs from when I was 19, just married. When you made casts of my body, my torso and face, my eyes and mouth were sealed, and I could not move my hands or arms. It was black under the cast. I was hoping to get out of this alive, intact. After all I was just starting over.

As participant and observer, I was attempting to intuit the finished work, attempting therefore to intuit the posterity of my body. I would emerge from the cast, living, to see the completed work from the outside. The intuiting body, the one still asleep but about to be awoken to the finished work, is what remains as sculpture, a cocoon always in the state of anticipating its waking to its next, its related form.